We Love Kimono Project 6

In early August 2020. Mamiya-san, my kimono retailer, received a “medashi 芽出し” from Katsuyama-san, the Obi maker. What is it? I had no clue.

Medashi is a trial sample that an obi maker weaves. Before making the complete obi, the maker weaves the main design pattern using the sample yarns. This way, any further requests or changes from the customer can be reflected in the course.

Mamiya-san tried to snail mail the medashi to me just like he did with the base color sample of the kimono fabric. (See We Love Kimono Project 3). However, due to the worsening pandemic, all the airmail from Japan to the US was suspended. Surface mail would take three or more months. We had no choice but to fall back on relying on digital photos this time.

The photo above is a close-up of the medashi. I noticed some light pink and gold colors were included together with the wisteria blue that was used as the anchor color. Starting in the center of the Islamic Flower design, different patterns radiated one after another. The yarn of the raised part looked thicker than the recessed part, but can it be? I was mesmerized by its complexity.

The back side shows you how many different yarns are used for making this one design.

I thought it was beautiful. Shall we move on? No, was Mamiya-san’s feedback. According to Mamiya-san, Katsuyama-san was overusing the colors. Is the gold thread really necessary? What about pink?

Since Mamiya-san has worked with Katsuyama-san many times before, Mamiya-san didn’t hold back his candid opinion. Let’s make it simpler, he suggested. That way Katsuyama-san’s true graceful design will be more prominent. Mamiya-san convinced Katsuyama-san to make a second try.

I asked Mamiya-san if I could still keep the first medashi. Sorry, Akemi-san. This is Katsuyama-san’s important property. He is to keep it so that he can reference it for his future work. It is less likely he will make exactly the same one. But it’s important that Katsuyama-san keeps all the medashi as his portfolio.

Soon after Mamiya-san sent me a photo of the first medashi, he sent me this photo. What is this? Are these the colors that Mamiya-san chose for my obi? I was horrified.

Don’t worry, Akemi-san. They are not the final colors, Mamiya-san assured me. These colorings are a necessary part of the weaving process.

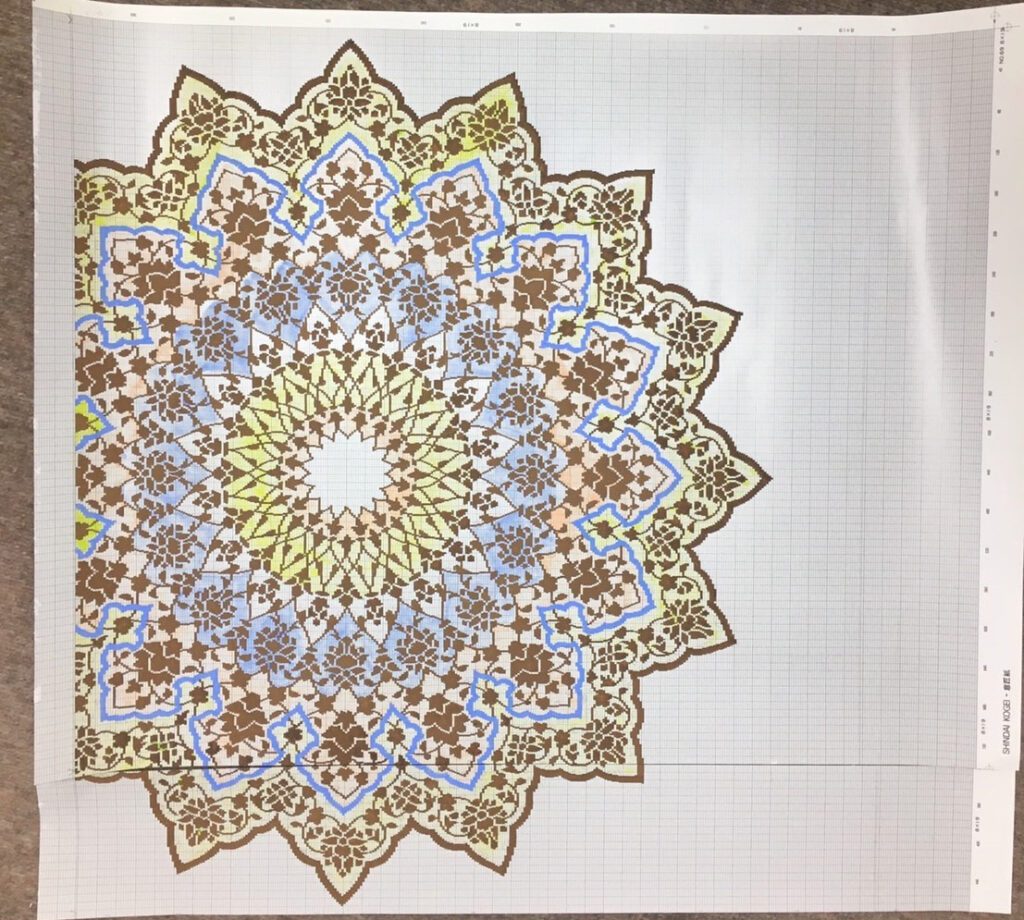

The Nishijin district in Kyoto implemented Jacquard looms from France in the late nineteenth century. Katsuyama-san’s weavers are trained in this technique. Katsuyama-san first draws and paints the obi design onto a paper grid. The photo above is of hand-painted grid design paper. Each column represents one warp yarn, and each row represents one weft yarn. In order to make sure that the weaver doesn’t get confused, the convention is to use distinct colors for each different color thread. The colors on this paper have nothing to do with the real colors.

This is the closeup of the grid paper.

Once drawing and painting on the grid paper is finished, Katsuyama-san scans it to a computer for two reasons. One is to create Jacquard punch cards; the other is to create another paper for weavers to use as a guiding source when s/he weaves this pattern.

This is the closeup of the Jacquard punch cards. Each card is narrow and long, indicating how each warp should be lifted so the weft can go through. Each card has eight rows, which are meant to control eight weft yarns. The cards are bound together with the white thread as shown.

I remembered a photo I took when I visited Katstuyama-san’s studio. The long rail of punch cards was hanging from the top of the loom. I never knew then, but that’s how they control the warp. I asked Mamiya-san how many cards were punched and put together like this for my obi. He replied: 9200 cards!

This is the reference paper that the weaver uses. She has a table that indicates which color on the paper corresponds to which color of the real yarn.

When I visited Katsuyama-san’s studio, the weaver was working on the obi with the diamond design. The paper shown here must have been her reference paper.

I heard that the Jacquard punch cards are replaced with computers nowadays. Why still use the physical punch cards, I asked. Because if a mistake is made, it is easy to find it with the punch cards and correct it right away.

Why hand loom instead of using a machine? According to the book Nishijin Ori – Nihon no Senshoku 11 published by Tairyusha (p. 77), a machine can handle up to ten different colors. If the obi uses more colors, a hand loom is a must. Some obis use over fifty different colors!

The book was written in 1976. Machine looms must have advanced quite a bit since then. But Katsuyama-san still chooses handloom, because this way each obi looks slightly different and has its own beauty that can’t be replaced with any other.

About four months after I received the first medashi photo, I got a photo of the second one.

The second medashi had no gold thread, no pink, but more subtle variations of blues and wisteria colors. The outer rim of the design is now a much lighter color. Mamiya-san said, let’s go with this one.

Mamiya-san will show this medashi to Kosaka-san so that Kosaka-san can determine the base color of the kimono. Kosaka-san will draw Yuzen design on the left shoulder and the bottom front of the kimono based on this medashi.

I asked Mamiya-san if Katsuyama-san always makes two medashis for an obi. Not normally. Since this project was an unusual collaboration, it was necessary to take an extra step. I appreciate the craftsman’s attention to detail. I bet Katsuyama-san pursues efficiency in his process. But sometimes efficiency gives way to the pursuit of perfection. I’m learning how a craftsman works.