Can they survive?

The word Nishijin 西陣 has multiple meanings.

The literal translation into English is “the Western Base,” a military jargon.

During the civil war called Onin no Ran 応仁の乱 (1467 – 1477), then the capital of Japan Kyoto became the battlefield of the two major samurai warlords. The neighborhood where the west squad placed its base was called Nishijin. The Onin no Ran and the wars that followed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries left Kyoto in ruins. Many people fled Kyoto during that period.

When the series of civil wars ended, people who had fled Kyoto gradually returned.

Skilled weavers and other craftsmen in the textile making who used to serve the imperial court and aristocrats also returned, settled, and resumed their crafts in the district where the Western Base was once located. Hence the word “Nishijin” became equivalent to Kyoto’s textile district, as well as meaning kimono and obi textiles that were woven in this district as a whole. Weavers in Nishijin district formed a tight-knit industry community, which also became identified as Nishijin.

During the Edo Era (1603 – 1868), Japan enjoyed more than 260 years of peaceful time under the Tokugawa Shogunate. With its exquisitely sophisticated techniques and high quality, Nishijin textile was sought after by the ruling samurai clan as well as by the imperial court and aristocrats. Nishijin flourished by providing them with top-of-the-line textiles for their luxurious attire.

The beginning of Meiji Era (1868 – 1912) was a challenging time for Nishijin. All of a sudden, its most prominent patron, the samurai clan, lost power because of the regime change, and the demand from the clan tanked.

That was when Nishijin sent three people from its weavers’ community to France to learn the newest technology, Jacquard Loom. Previously Nishijin used to employ a technique that required two people to handle one loom. Jacquard Loom, on the other hand, required only one person to handle it.

By implementing Jacquard Loom, Nishijin was able to boost its productivity as well as diversify its product lines to meet the need of a wider audience, the general public.

With the rapid expansion of Japan’s economy after World War II, Nishijin enjoyed high growth. Nishijin became a synonym for high-quality obis among common people like my mother. She didn’t have to ask further if the retailer indicated that the obi was “Nishijin.”

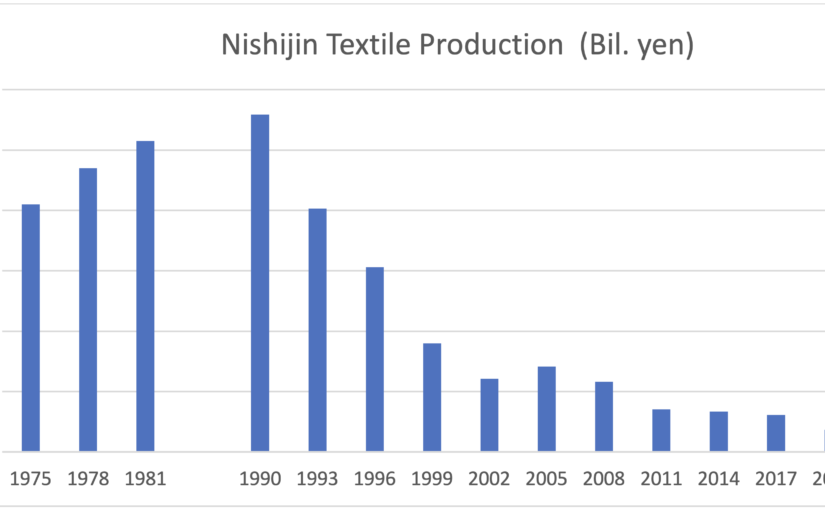

In the late 1980’s. Japan’s economy was having its hay day. So did Nishijin. “Gacha-man” is a word I learned from a friend of mine who grew up in Nishijin. “Gacha” imitates the sound of a Nishijin weaver moving the loom to add one weft. “Man” is a short form of ichiman, or ten thousand yen, roughly a hundred dollars. According to my friend, a weaver would earn a hundred dollars each time s/he moves one weft. This expression depicts how prosperous Nishijin once was.

During the economic bubble, national kimono chain stores started to appear and soon became dominant, replacing many smaller independent retailers. Many such stores took advantage of the ignorance of their customers, rather than taking time to educate them. Hiring many salespeople who didn’t have much knowledge of kimono, such chain stores employed aggressive sales tactics. They manipulated gullible customers to purchase a grossly marked-up, expensive kimono of questionable quality.

A set of kimono and obi would often be priced as much as a brand-new car. And just like buying a car, many customers were obliged to pay in installments. The aggressive sales tactics of kimono chain stores became so notorious that even TV channels created documentaries about their practice to warn people.

I was recently out of college and working for an investment bank in Tokyo around that time. Purchasing business suites was my top priority so I paid little attention to kimono. Even if I was slightly interested in trying out kimono, having heard of horror stories, I was too intimidated to enter those big kimono stores I found here and there in downtown Tokyo.

Then the economic bubble burst in 1990. Japan’s so called “Lost Decade” became “Lost Decades” and is now stretching over three decades. Kimono production plunged over the years, and so did textile production in Nishijin. Many such national chain kimono stores went bankrupt. Also there were far fewer independent kimono retailers left.

The chart above is what I found on the Nishijin Textile Industry Association website. The production of Nishijin’s textile is less than 10% of the hay days. In such a dire situation, can Nishijin survive?

In the course of pursuing my favorite kimonos and obis, I have met several people in Nishijin who are doing everything they can to survive and thrive. I will keep on writing about what I encounter…