When and how I chose my obi

Ever since I met her for the first time in the spring of 2016, it became my routine to see Reiko-san, the CEO of Rakufulin 洛風林, whenever I went back to Japan. For a couple of years, I never had a chance to be in Japan during Rakufulin’s annual exhibition. In the spring of 2019, I finally was able to visit Kyoto in time for their annual exhibition.

The theme of that year’s exhibition was “kissako喫茶去.” Like all the other Zen phrases, it’s not easy to translate it into English. A literal translation is “Why don’t you have a bowl of tea?”

Dressed in that matcha color kimono that I had selected at Katsuyama-san’s studio, I went to the annex building of the Kyoto City Internation Foundation, where the exhibition was held.

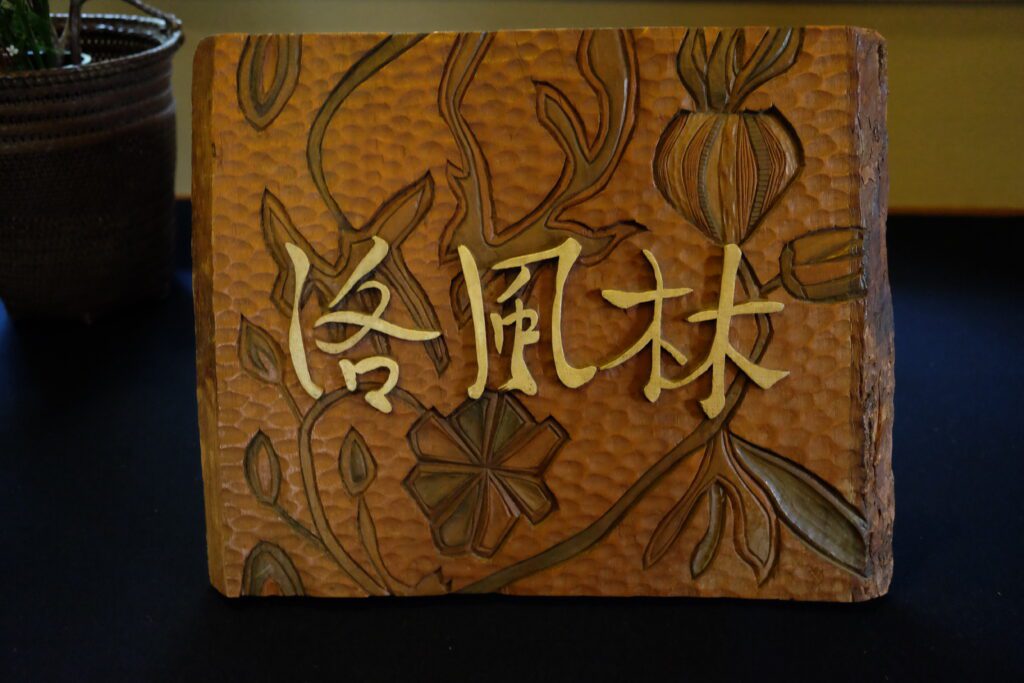

The venue was a Japanese-style building. At the entrance, I took off my shoes, placed them on the large shelf on the wall, and stepped up onto the raised floor. I saw an old wood sign with the company name 洛風林(Rakufulin) hand-carved into it together with a vegetable or flower design with vines.

Then I turned right and followed the narrow, hardwood-floor hall. At the end of the hall were two rooms with tatami mats.

On the right side of the corridor, half of the room was staged as the study of Mr. Takeshi Horie, the founder of Rakufulin and Reiko-san’s grandfather. The very low desk and the round low table that Horie-san used to sit at were brought in. Several sample books and fabrics that Horie-san had collected from his trips were displayed alongside the desk, as if he were still working there.

According to Reiko-san, Horie-san used to sit at the round table with his partner weaver, and discuss the design details of the Obi. Katsuyama-san’s father or grandfather would have sat around this table as well.

I asked Reiko-san and Aiko-san, Reiko-san’s younger sister and Rakufulin’s chief designer, to take seats in front of the table. Reiko-san was wearing a dark-colored Kimono. She told me that she had her father’s kimono remade.

I noticed that when Reiko-san and Aiko-san talk about their grandfather, they mostly refer him as “Shodai初代,” which means “first generation.” Likewise, they would most often refer to their father as “Sendai先代,” meaning “previous generation.” Although biologically they are their grandfather and father, when it comes to talking about business, calling them Shodai and Sendai sounds more appropriate and professional.

When Reiko-san uses the word Shodai, I see and feel the huge responsibility that she has chosen to carry on her shoulders. I look at her not only as my friend Reiko-san but also as Todai当代, the current generation of Rakufulin.

When Reiko-san took over the family business, the kimono industry was no longer the same as when Sendai was running it. Japan’s economic bubble had already burst, and Kimono’s glory days were in the past. She had to make some major changes to the business operation.

Streamlining the sales channel was one thing. She had to review the existing retailers and sever relationships when necessary. She also had to deal with copycats sold as Rakufulin’s products in the market. Reiko-san must have gone through difficult situations, but her smile and soft-speaking voice made it hard for me to imagine her tough negotiation battles.

On the opposite corner of the toom, older Obi that Shodai and Sendai designed were displayed. Some of them must be half a century old. They were all gorgeous, with so many different colors and complex patterns. Some of them can no longer be replicated because no weavers with such high skills are remaining.

Two sides of the other tatami-mat room were filled with the newer Obi. Some formal; some casual. Some with design patterns all through; some with designs only on the spot. Each Obi design had its own name. Some were typical Japanese names like “Ancient Flowers.” Some had exotic names like “Silk Road” or “Sarasen Circle.”

I looked at each Obi closely with the intention of selecting one to get. The Obi should match very well with the matcha-color kimono I was wearing, but it should also be versatile enough to match some of my other kimonos as well.

In order to match as many different colors as possible, I thought the base color of Obi should be white or a very light, neutral color. Why only one, you may ask. Of course I wish I could get many more! But my wallet was saying no.

My choice was a whitish obi, called Sarasen Circle. It has a big spot design on the back, and a smaller circle is placed on the front. Blue is rather dominant, but there is a little yellow in the middle of the circle. The shape of Obi, called a fukuro obi, is formal enough to be able to wear on different occasions including tea gatherings.

After I kind of made up my mind, I asked Reiko-san her opinion. As an all-purpose obi, which one would she recommend for me?

Reiko-san’s answer was far from my choice. She took me to the one I most overlooked.

Called Ichimatsu, this obi’s base color is black. Gold and silver squares are placed alternately. This design is not a new one, but one of Shodai’s original designs inspired by a fusuma painting in Katsura Imperial Palace in Kyoto.

Such a simple design, with timeless beauty.

Reiko-san also told me that this obi was a collaboration of Katsuyama-san and Saito-san. The real gold and silver. How can I say no to this obi?

…

I’m glad that I followed Reiko-san’s advice! Here in Seattle, I now wear this Ichimatsu obi most often. Thank you, Reiko-san! Now I’m convinced. My kimono and obi are my jewelry.