So I was taught at school

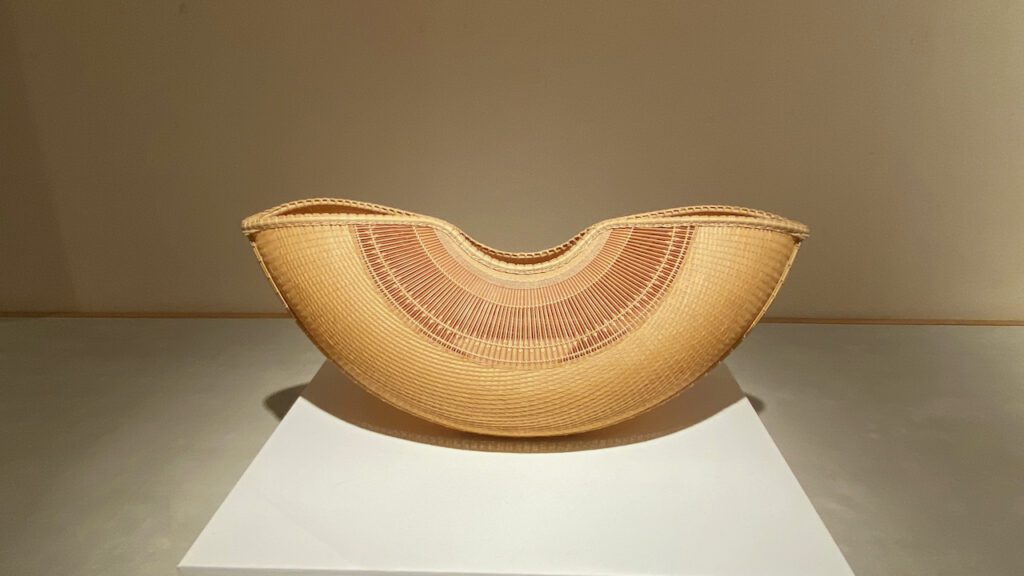

Photo: Genjimonogatari Emaki by Wikipedia

I first learned about Hyakunin Isshu 百人一首, a classical Japanese anthology of one hundred waka poems by one hundred poets compiled in the 13th century, in junior high school. Learning Hyakunin Isshu meant learning about the sex life of ancient Japanese aristocrats and court ladies.

In ancient Japan,

- virginity was not highly valued by men or women.

- monogamy was not highly valued, either.

- a man visits a woman at her house at night and goes home at dawn.

The sunrise, therefore, was a departing time for lovers. And if a woman makes a poem about sleeping alone at dawn, she must be full of jealousy.

The following 5 poems are examples of such love poems in Hyakunin Isshu.

21/100 素性法師 by Sosei Hoshi

今こむと Ima kom to

言ひしばかりにIishi bakari ni

長月の Naga-tsuki no

有明の月をAriake no tsuki

待ちいでつるかなWo machi izuru kana.

The following is the English translation by William N. Porter (1909).

THE moon that shone the whole night through

This autumn morn I see,

As here I wait thy well-known step,

For thou didst promise me—

‘I’ll surely come to thee.’

30/100 壬生忠岑 by Mibu no Tadamine

有明の Ariake no

つれなく見えしTsurenaku mieshi

別れより Wakare yori

暁ばかりAkatsuki bakari

うきものはなしUki-mono wa nashi.

The following is the English translation by William N. Porter (1909).

I HATE the cold unfriendly moon,

That shines at early morn;

And nothing seems so sad and grey,

When I am left forlorn,

As day’s returning dawn.

52/100 藤原道信朝臣 By Fujiwara no Michinobu Ason

明けぬれば Akenureba

暮るるものとはKururu mono to wa

知りながら Shiri nagara

なほ恨めしきNao urameshiki

朝ぼらけかなAsaborake kana.

The following English translation is by Clay MacCauley (1917)

Like the morning moon,

Cold, unpitying was my love.

Since that parting hour,

Nothing I dislike so much

As the breaking light of day.

53/100 右大将道綱母 by Udaisho Michitsuna no Haha

歎きつつ Nageki-tsutsu

ひとりぬる夜のHitori nuru yo no

明くるまは Akuru ma wa

いかに久しきIkani hisashiki

ものとかは知るMono to kawa shiru.

The following is the English translation by William N. Porter (1909).

ALL through the long and dreary night

I lie awake and moan;

How desolate my chamber feels,

How weary I have grown

Of being left alone!

59/100 赤染衞門 by Akazome Emon

やすらはでYasurawade

寝なましものをNenamashi mono wo

小夜ふけて Sayofukete

かたぶくまでのKatabuku made no

月をみしかなTsuki wo mishi kana.

The following is the English translation by William N. Porter (1909).

WAITING and hoping for thy step,

Sleepless in bed I lie,

All through the night, until the moon,

Leaving her post on high,

Slips sideways down the sky.