We Love Kimono Project 5

Kimono made of silk is more formal than cotton or linen kimono. Not all the silk kimono, however, is made equal.

Silk kimono is categorized into two groups based on how the fabric is made.

One type is called Sakizome先染or Ori 織. The yarns are dyed first, usually the warp and the weft yarns separately, then they are woven. The most famous Ori kimono is Oshima Tsumugi 大島紬. With the intricate patterns and painstaking process, Oshima Tsumugi is one of the most expensive kimono fabrics in Japan.

Another type is Some 染. The undyed yarns are woven first, hence making natural-white color kimono fabric first. The fabric is then dyed in different colors and patterns.

Some 染 kimono is always considered more formal than Ori 織 kimono. For formal tea gatherings, Ori kimono is too casual, no matter how expensive it may be.

Once he had sketched a rough design of my kimono, Mamiya-san, my kimono retailer, selected the dyeing method of the kimono fabric. His choice was Yuzen hand dyeing 手描き友禅, and approached Kosaka-san, a Kyoto-based Yuzen kimono producer.

According to Mamiya-san, Kosaka-san’s name came to his mind right away when we agreed to launch We Love Kimono project. While Kosaka-san has a long experience of working with traditional Yuzen craftsmen, he tries to incorporate contemporary elements in the design. Kosaka-san will be willing to take up this challenging project, Mamiya-san thought.

What is Yuzen hand dyeing? A short video below shows you its process.

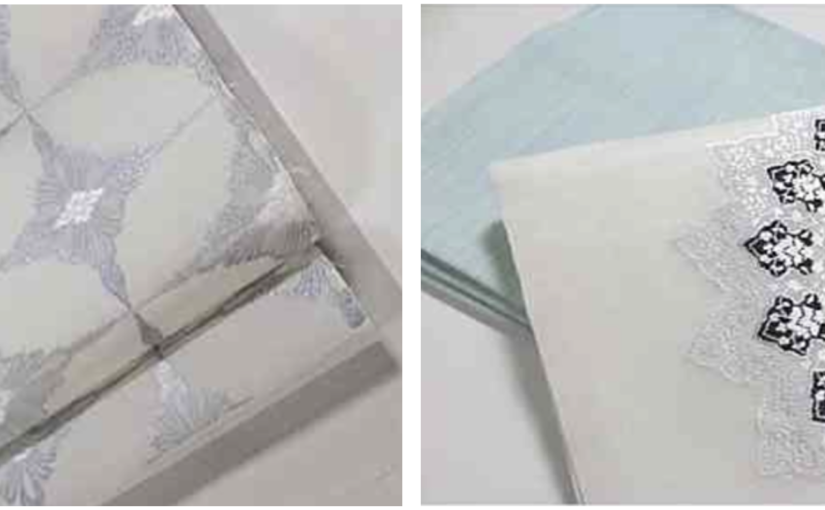

With the rough sketch he drew and a photo of Katsuyama-san’s Islamic Flower obi, Mamiya-san met with Kosaka-san. Mamiya-san’s idea was to replicate the obi’s Islamic Flower design onto the kimono. How large, where, and how similar the design should be on the kimono, was left up to Kosaka-san.

Kosaka-san getting introduced to the obi and kimono design.

After meeting with Kosaka-san, Mamiya-san went on to meet with Katsuyama-san to further discuss the project.

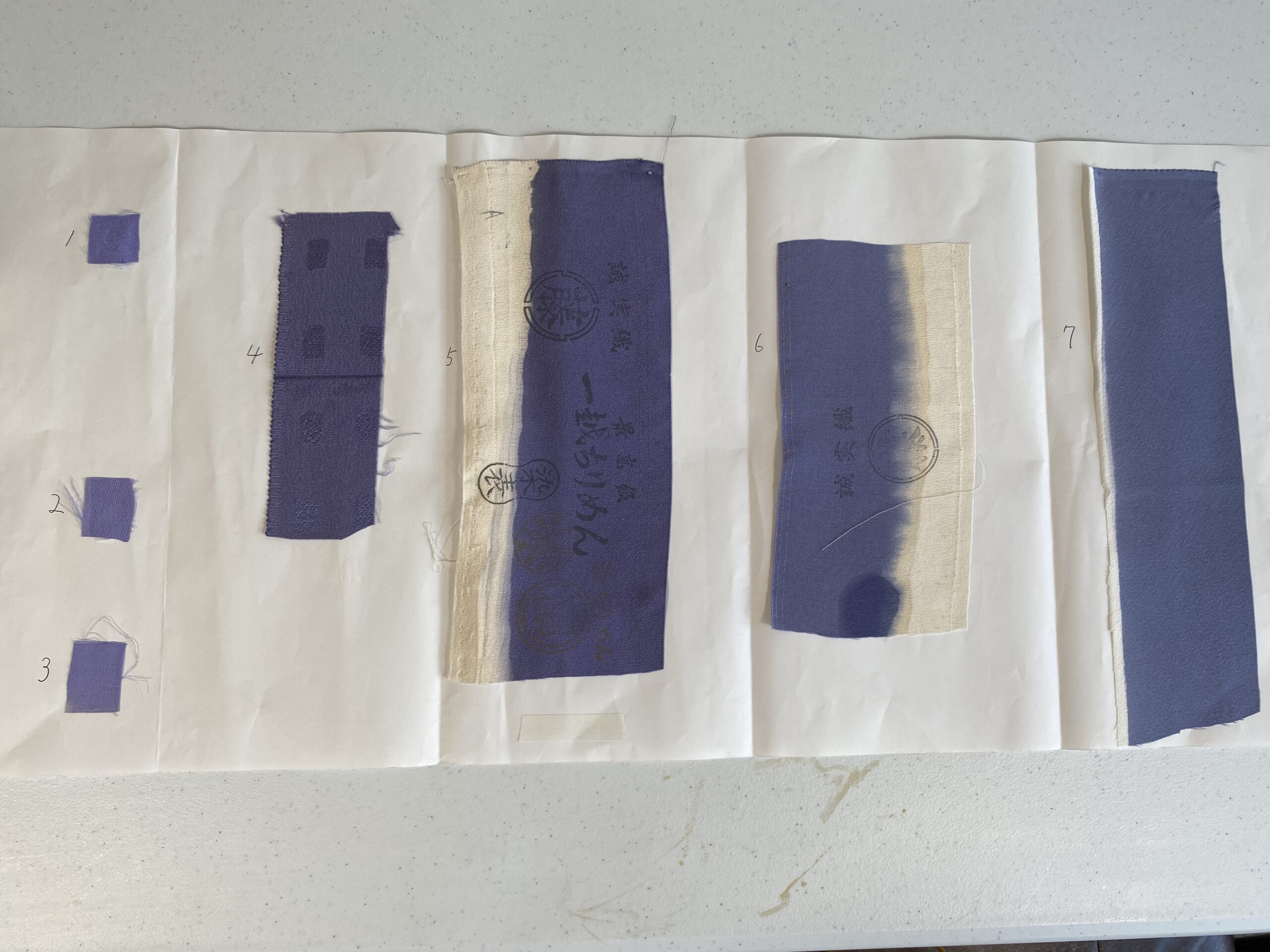

Mamiya-san showed Katsuyama-san the rough design of the kimono as well as the base color. The obi’s basic design is already selected, but the color combination is limitless. Does Katsuyama-san want to use the same color on the kimono and the obi? Or does he want to choose a matching, but slightly different color? Or will he choose contrasting colors?

Mamiya-san told me that it is not easy to dye the obi thread exactly the same color as the kimono. With obi, they dye the thread first then weave. With Yuzen kimono, they place colors onto the white silk fabric that is already woven. Since the order of dyeing and weaving is different, the final look of the color varies even though they use the same pigment.

For this project, Katsuyama-san would weave the obi first using the base color as the anchor color. Once the obi is woven, Kosaka-san would dye the kimono fabric while closely looking at the completed obi.

After talking to both Kosaka-san and Katsuyama-san, Mamiya-san slightly altered the kimono design. I had no objection. I was just thankful that I had these experienced craftsmen taking the time and effort to make my kimono and obi.