It starts with planting mulberry trees

On a sunny day in February, at the rotary of a train station in Kyoto, I met Katsuyama-san, a fifth-generation Obi maker in Nishijin, and Reiko-san, for the first time. Marusugi-san, the person who introduced me to Katsuyama-san, also showed up. We all got in a van and drove off.

Marusugi-san is a third-generation kimono and silk fabric retailer. She had traveled to Seattle in the previous year in an attempt to promote their new product lines that use ultra-thin silk fabric and gold film. I had helped her host a series of trunk shows in several places in Seattle. We agreed to meet again on my next trip to Japan, hence this reunion in Kyoto.

Katsuyama-san’s van headed north. Kyoto is bordered on three sides by mountains, so the further we went, the road became narrower and more winding.

The conversation in the van was mainly me talking.

“You know, the fabric you (I meant both Marusugi-san and Katsuyama-san) are selling is too expensive for clothing,” I said. “Why don’t you position the fabric as art? Why don’t you frame it and sell it through interior designers? American homes are large and they’ve got huge walls, which they have to decorate anyway.”

“Why stick to only kimono and obi? If you want to expand the market outside of Japan, expand the category. Wealthy Americans spend far more money than Japanese for their home decoration. I’ve seen so many Americans hanging vintage kimono or obi as a tapestry on the wall.”

Katsuyama-san nodded but didn’t say much.

The van stopped in front of a one-story building in the middle of a rice field. We all got out of the van and followed Katsuyama-san into the building. On the left there was a tatami-mat room, maybe twelve tatami mats in total. On one side of the room there were wall-to-wall shelves and drawers. On the other side of the room, there were stacks of flat boxes.

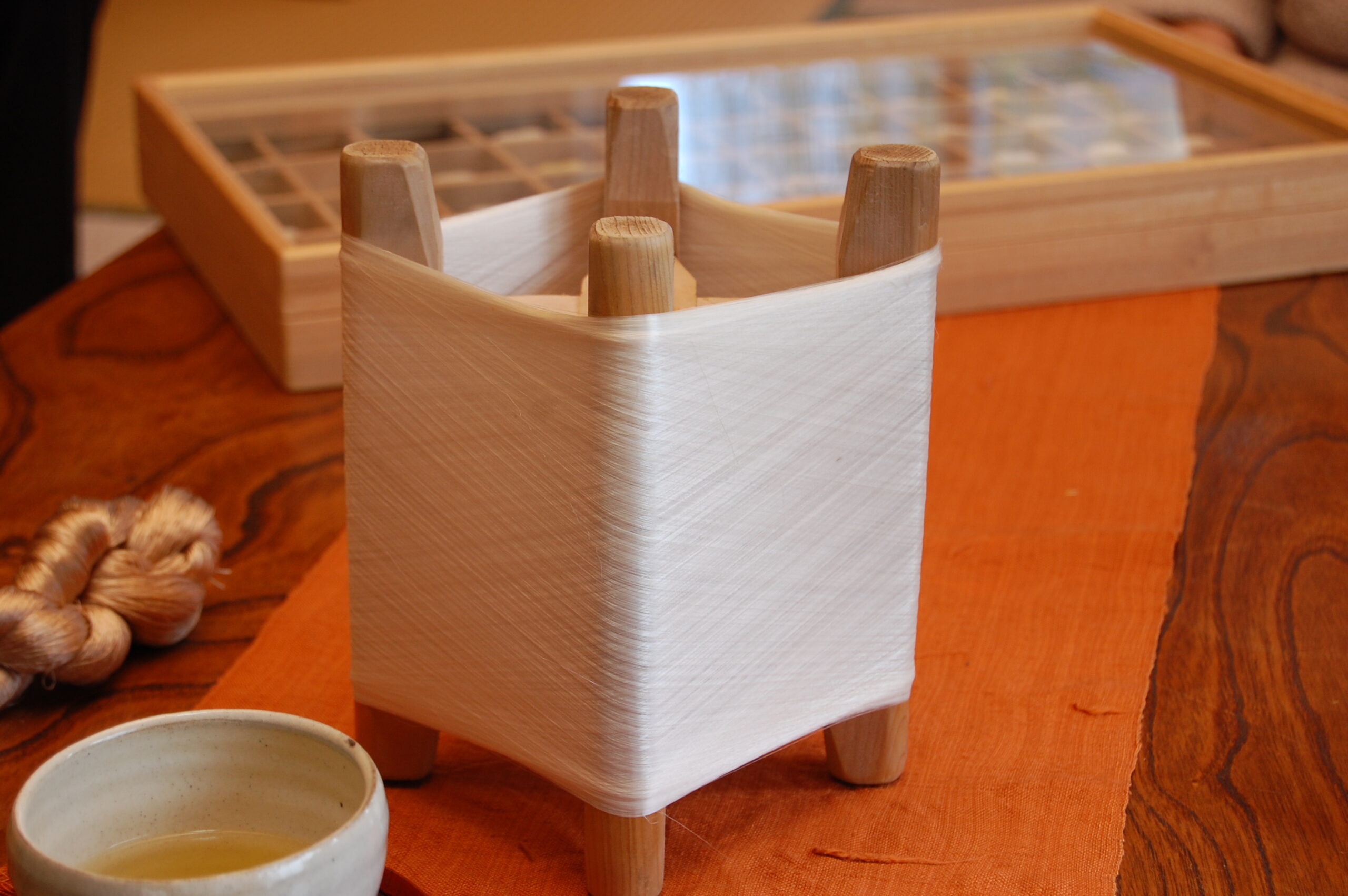

Katsuyama-san took out two bundles of thread and let me touch both. The first one was softer and less shiny, but depending upon the angle, it reflected the light differently. It felt ideal in my palm. The threads of the second bundle looked all even, but didn’t have that rich texture.

The woman in the black jacket was introduced to me as Reiko Horie, CEO of Rakufulin洛風林, the company that sells Katsuyama-san’s obi.

While I was still enjoying the softer texture of the first bundle of silk threads, Reiko-san (I use her first name because we are now good friends) started to explain what I was touching. It was the silk thread made by Katsuyama-san’s company based in Nagano Prefecture. In 2003 Katsuyama-san obtained property there and started growing mulberry trees to raise silkworms.

Katsuyama-san used to use imported silk (the bundle I liked less). One day he was asked by a national museum to work on the restoration of the fabric made in the fifteenth century. The silk fabric was nothing like he had ever seen before. Soft, light, graceful — ever since then he couldn’t forget that fabric.

When he visited Milan, Katsuyama-san encountered the same type of silk fabric in a men’s handkerchief. Quite impressed, he asked the shopkeeper where the fabric was made. Not in Italy, but it was made in Japan, was the answer.

Katsuyama-san did further research and found the person who made the handkerchief fabric, Shimura-san. After a lot of persuading, Katsuyama-san successfully invited Shimura-san to be the co-founder of his silk farm. Shimura-san moved from Okinawa to Nagano.

What is the difference between Katsuyama-san and Shimura-san’s silk and other silk? It’s in the kind of mulberry they grow. In their farm they grow two kinds of mulberry trees. They feed the silkworms only the younger, softer leaves. Shimura-san found through his years of research that it helps silkworms to produce thinner but stronger silk.

Once the silkworms create cocoons, their lives end before they come out of the cocoons. Today’s main method of taking the lives of silkworms in the cocoons is to blow extremely hot air into the cocoons. The hot air eliminates humidity, making it easy to store the cocoons. The silk’s natural texture, however, is somewhat lost.

Shimura-san found a more natural and time-tested alternative: to salt the cocoons. Shimura-san places cocoons in a wooden barrel and salts them for two weeks. This way the silk’s natural texture and strength is maintained.

Making silk yarn as well as dissolving the sericin is done by hand at their farm.

In the same farm where they grow mulberry and silk cocoons, they make silk yarn and weave the kimono fabric. Shimura-san uses mostly natural dyes extracted from local plants. The main reason Shimura-san decided to join Katsuyama-san in Nagano is because he can be involved in the whole process in one place, giving him complete quality control of his products.

Katsuyama-san quietly said, “I’m making fabric that is to be worn.” I felt ashamed of what I had said in the van.