Day 7 of 30-Day Writing Challenge

The latest movie I watched has become my favorite.

David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet

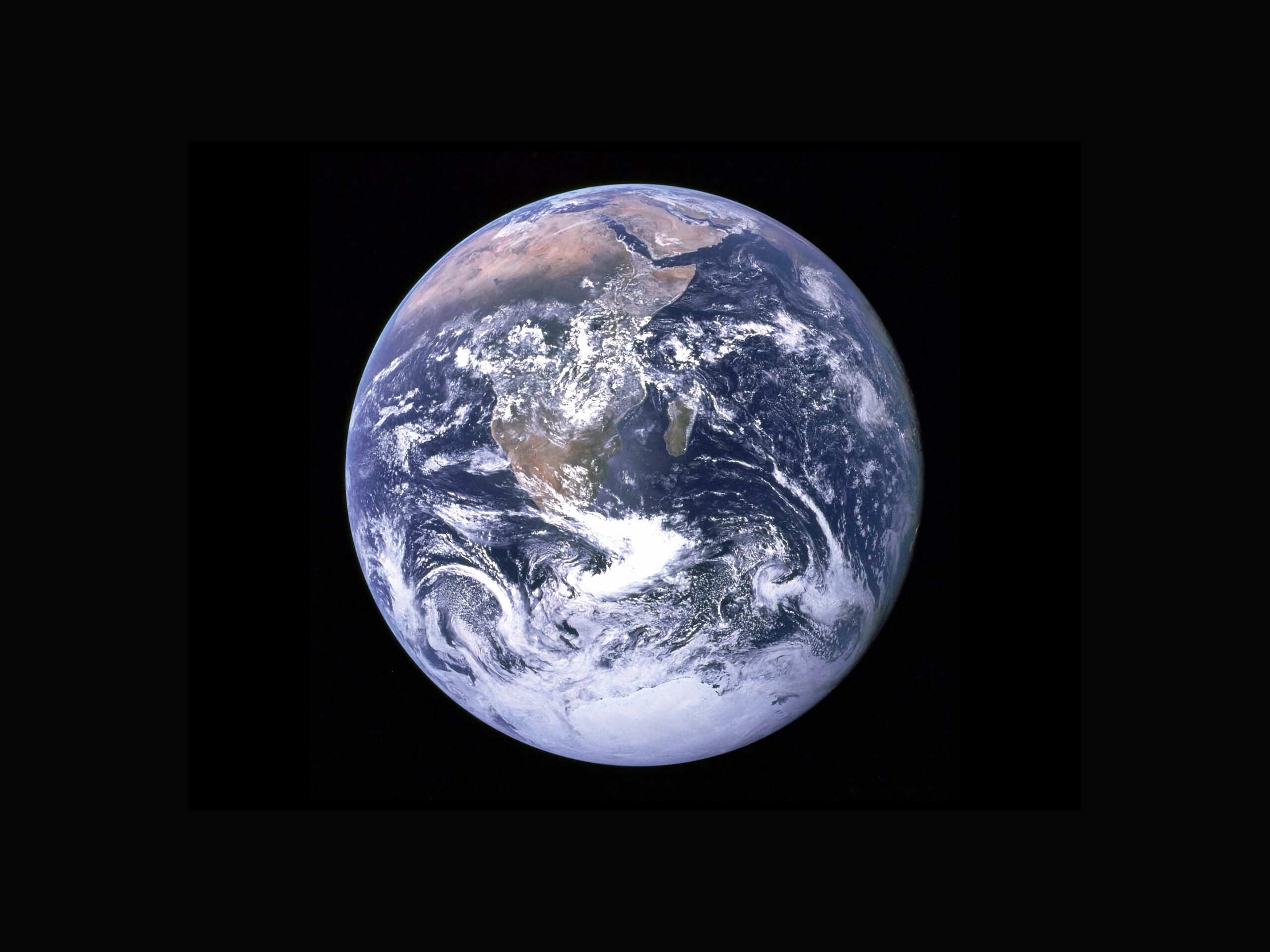

In the beginning of this movie, Sir David Attenborough says this documentary is his witness statement. A witness statement of a crime that we human beings have committed.

In case you don’t know about him, here is an excerpt from his page on Wikipedia:

“Sir David Frederick Attenborough (/ˈætənbərə/; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural history documentary series forming the Life collection, a comprehensive survey of animal and plant life on Earth.

On his broadcasting and passion for nature, NPR stated he “roamed the globe and shared his discoveries and enthusiasms with his patented semi-whisper way of narrating”. He is widely considered a national treasure in the UK, although he himself does not like the term.

Wikipedia

I have to confess that it is only recent, maybe within a year or so since I learned about his work and career.

My attempt to write about Japanese traditional culture led me more and more interested in its sustainable lifestyle. The lifestyle my ancestors used to have for centuries before the wave of Industrial Revolution swept Japan. Words such as “nature” or “living in harmony” became keywords I would more often type together with “Japan” or “Japanese traditional culture.”

Ever evolving AI technology must have figured out that I should be connected to Sir Attenborough’s work. Short movies or snippets of his BBC Natural History documentaries started popping up on my computer screen. For this encounter I have to thank AI.

The only TV at home is usually occupied by my husband. My husband ‘s favorite program has less than 0.5% in common with mine, so whenever he watches TV I put on my earphones and place my eyes on my laptop. Only when my husband is away, out of boredom and a little sense of freedom I pick up the TV remote and push the mic button and say “Netflix.”

On such a night when I was browsing the documentary section, this movie came up. I clicked play and started watching it.

From the beginning till about a couple of minutes before the ending, the story made me almost cry, filled with despair. But at the age of 94, Sir Attenborough must have made this movie because he still has hope that we human beings can change the course. The last scene when crowd of people somewhere in Japan enjoying Hanami (viewing of cherry blossoms) had me.

His final message in this movie was that we human beings are not apart from but are a part of nature. If he depicts his message with this scene, it’s worth my continuing to write about it. To remind us to live in harmony with nature. And there are so many examples in Japan’s traditional culture that we can make use of in our current lifestyle.