Why I couldn’t choose one

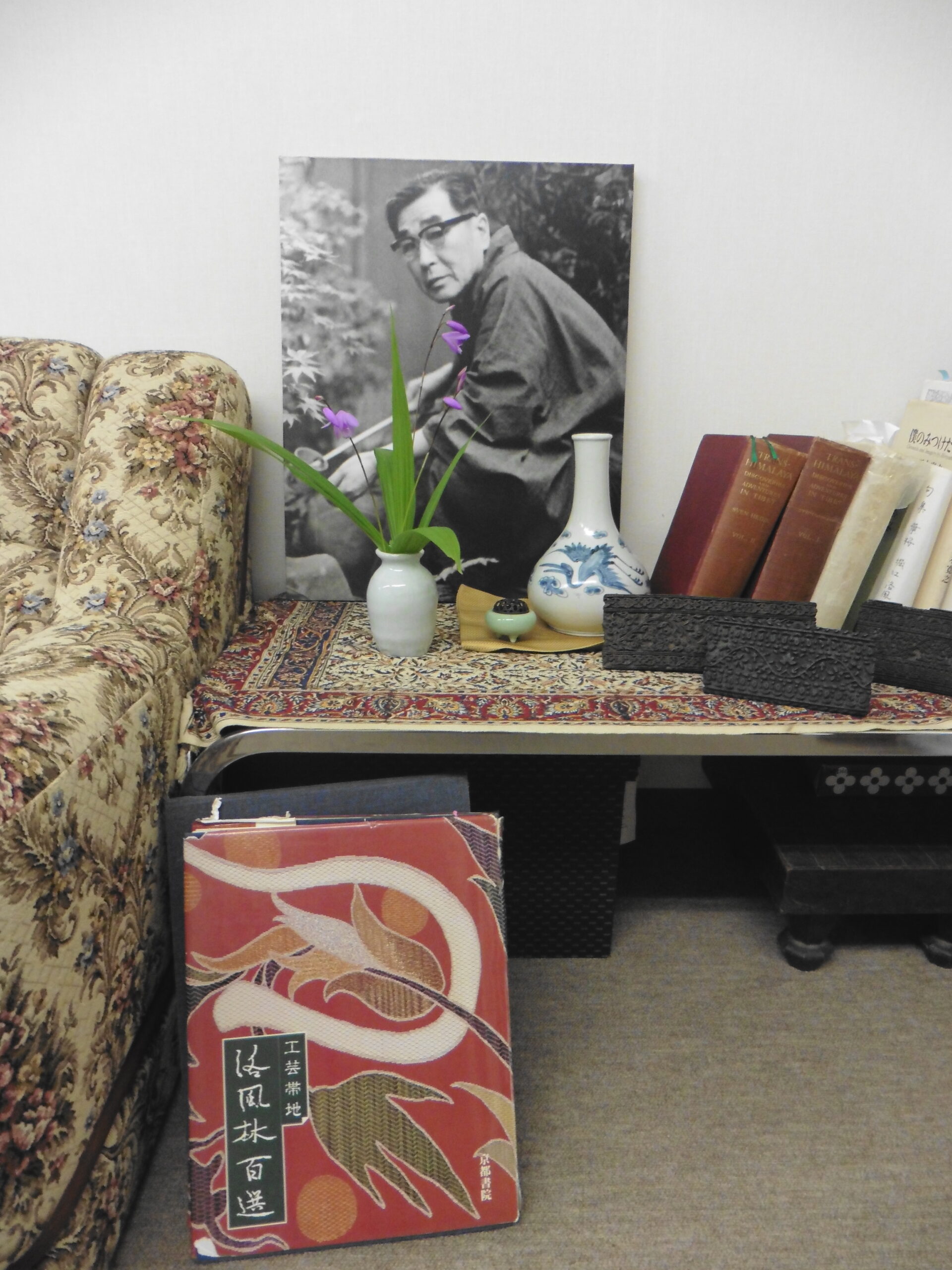

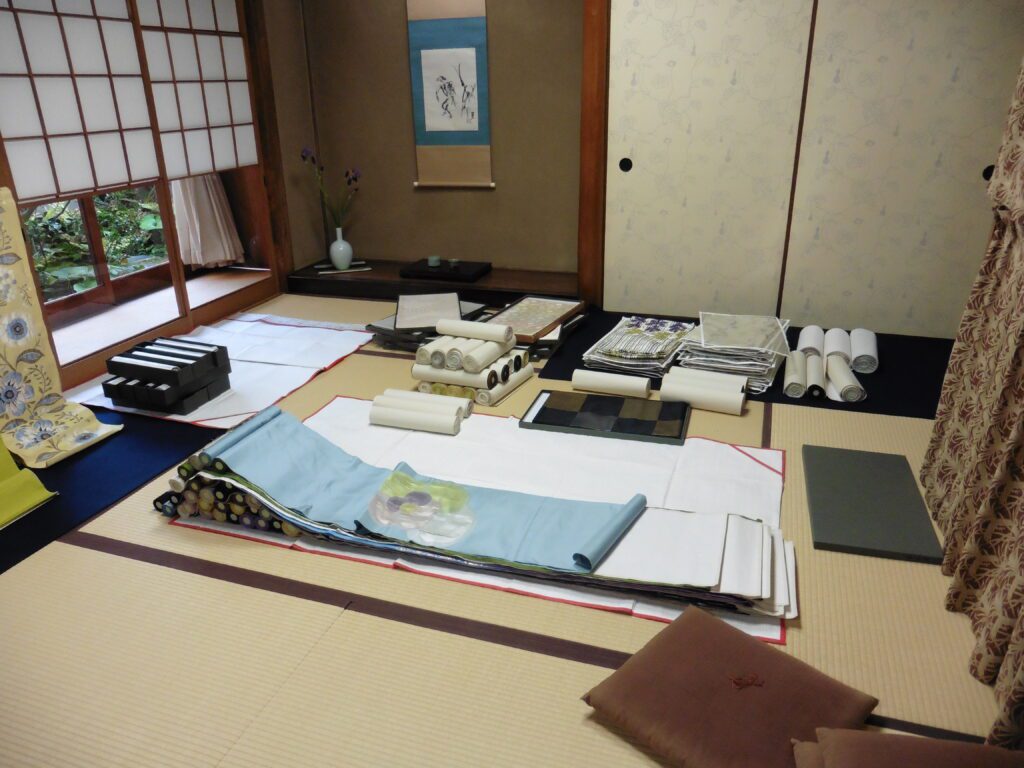

Several days after we visited Katsuyama-san’s studio, I paid a visit to Rakufulin’s office in the center of Kyoto. Reiko-san greeted me with a warm smile and led me to the tatami-mat room where some of Rakufulin’s Obi were displayed and many more stacked.

She first told me a story about her family business, then began spreading Obi one by one.

Many of the Obi designs were traces of the fabrics that Reiko-san’s father and grandfather gathered from all over the world, especially in central Asia. Aiko-san, Reiko-san’s younger sister and the chief design officer of Rakufulin, adds her own interpretation to the original designs and creates new Obi.

Let me share with you some photos I took!

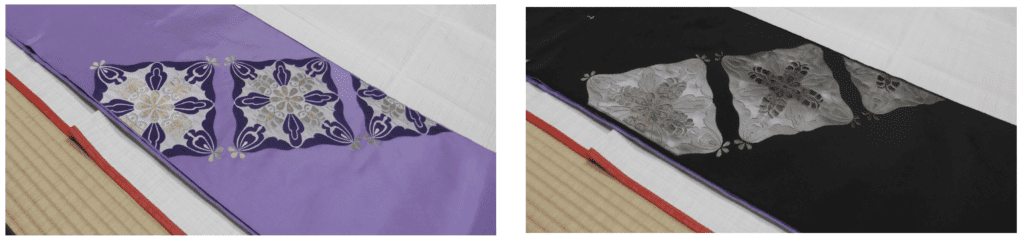

Below are examples of color magic. The two Obi shown side-by-side are the same design. By applying different colors, each Obi gives you quite different impressions.

The following two Obi employ the fukure ori ふくれ織 technique. The flower part is a little puffier than the rest, giving you a three-dimensional impression.

Aiko-san also designed these Obi. Her color selection reflects the contemporary trend.

Among more than 30 Obi that Reiko-san showed me on that day, this one was my favorite.

The orange flower looks like Dahlia, is it? Is the flower with the purple outline Iris? How about the bluish flower with five petals? You can’t make out which flowers exactly, but each gives you a whimsical impression. Various shapes of leaves and vines are dancing all over. And the background has also various patterns including large horizontal stripes and smaller vertical stripes.

How many colors are used in total? So many. Each color is inviting, looking so sweet. I almost want to put it in my mouth like candy. I can’t find any dominant color or pattern, but this Obi definitely gives you a sophisticated, overall harmony.

The problem I had, however, was I couldn’t think of any of my kimono that would match this Obi.

You know, Obi is only one component for dressing. It’s rather an accent. You need the main foundation, which is Kimono. What kind of Kimono will have enough significance that can treat this Obi as a mere accent? I couldn’t find any in my humble Kimono collection. A big sigh.

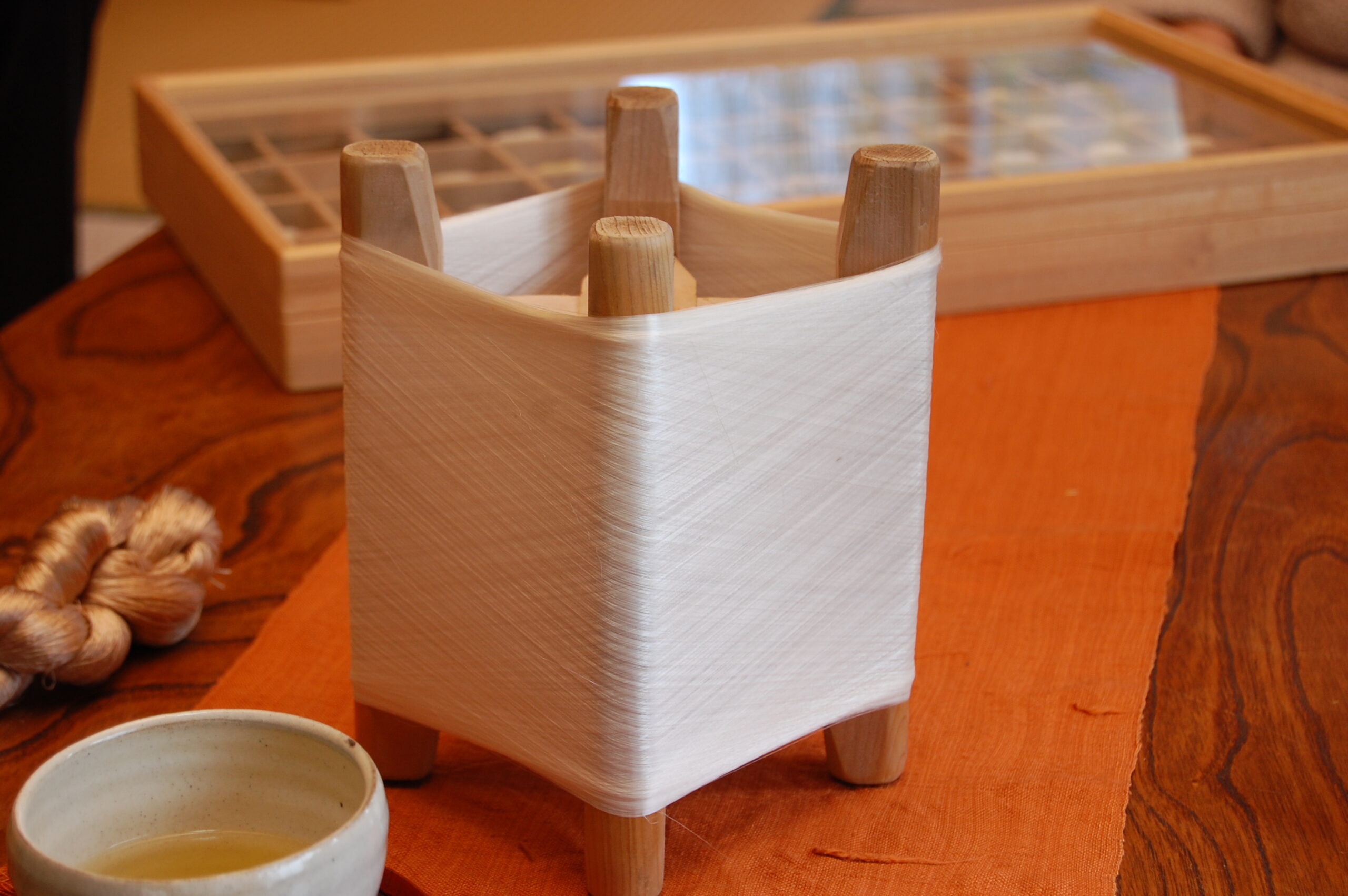

After spreading the Obi to show it to me, Reiko-san kept laying one on top of the other. By the time she showed me close to thirty, the pile of Obi fabrics formed a beautiful pyramid. At Rakufulin, even how Obi are shown on the tatami-mat floor becomes artistic!