There are 12 out of 100!

Photo by Author Akemi Sagawa

Moon is a mystery to me. Most of the time when the moon is shining in the sky, I’m asleep. With the convenience of electricity, I no longer have to depend on the moonlight to study or read at night.

So whenever I read poems written by ancient people, I’m awed by their close attention to the moon. Before the sky was invaded by artificial brightness, the moon must have been much more intimate in people’s lives.

Hyakunin Isshu (百人一首)is a classical Japanese anthology of one hundred waka poems by one hundred poets compiled by Fujiwara no Teika (藤原定家 1162 – 1241). The selection ranges from as old as the one written by Emperor Tenji (626 – 672) to Teika’s contemporary.

I’m not a competitive player of Hyakunin Isshu card game, but I can still recite some of the poems.

Here is a list of 12 poems in Hyakunin Isshu that read about the moon. The English translation is according to William N. Porter which is published in 1909.

Since I only memorized them in Japanese, it’s a great opportunity to refamiliarize these poems in English translation. Here you go!

7/100 阿倍仲麻呂 – Abe no Nakamaro

天の原ふりさけ見れば春日なる 三笠の山に出でし月かも

WHILE gazing up into the sky,

My thoughts have wandered far;

Methinks I See the rising moon

Above Mount Mikasa

At far-off Kasuga

21/100 素性法師 – Sosei Hoshi

いま来むと言ひしばかりに長月の 有明の月を待ち出でつるかな

THE moon that shone the whole night through

This autumn moon I see,

As here I wait thy well-known step,

For thou didst promise me—

‘I’ll surely come to thee.’

23/100 大江千里 – Ooe no Chisato

月見ればちぢにものこそ悲しけれ わが身一つの秋にはあらねど

THIS night the cheerless autumn moon

Doth all my mind enthrall;

But others also have their griefs,

For autumn on us all

Hath cast her gloomy pall.

30/100 壬生忠岑 – Mibu no Tadamine

有明のつれなく見えし別れより 暁ばかり憂きものはなし

I HATE the cold unfriendly moon,

That shines at early morn;

And nothing seems so sad and grey,

When I am left forlorn,

As day’s returning dawn.

31/100 坂上是則 – By Saka-no-Uye no Korenori

朝ぼらけ有明の月と見るまでに 吉野の里に触れる白雪

SURELY the morning moon, I thought,

Has bathed the hill in light

But, no; I see it is the snow

That, falling in the night,

Has made Yoshino white.

36/100 清原深養父 – Kiyohara no Fukayabu

夏の夜はまだ宵ながら明けぬるを 雲のいづこに月宿るらむ

TOO short the lovely summer night,

Too soon ‘tis passed away,

I watched to see behind which cloud

The moon would chance to stay,

And here’s the dawn of day!

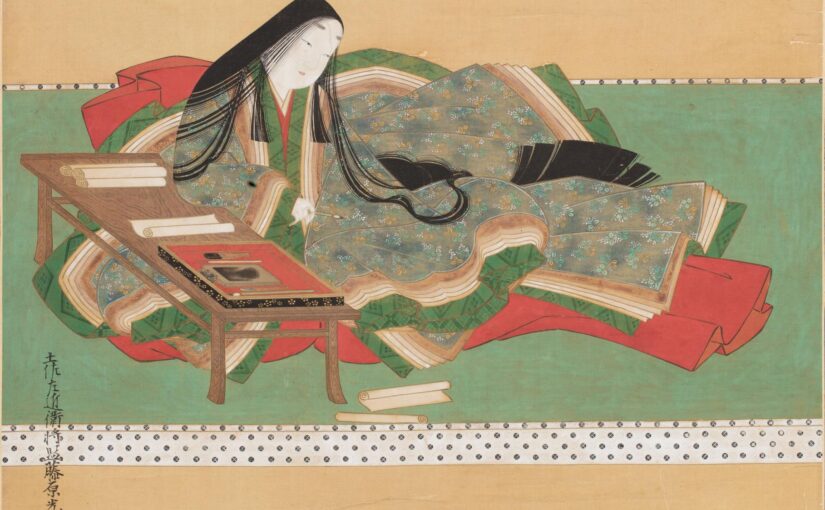

57/100 紫式部 – Murasaki Shikibu

めぐりあひて見しやそれとも分かぬ間に 雲隠れにし夜半の月かな

I WONDERED forth this moonlight night,

And some one hurried by;

But who it was I could not see,–

Clouds driving o’er the sky

Obscured the moon on high..

59/100 赤染衛門 – Akazoe Emon

やすらはで寝なましものを小夜更けて かたぶくまでの月を見しかな

WAITING and hoping for thy step,

Sleepless in bd I lie,

All through the night, until the moon,

Leaving her post on high,

Slips sideways down the sky.

68/100 三条院 – Sanjo In

心にもあらでうき世に長らへば 恋しかるべき夜半の月かな

IF in this troubled world of ours

I still must linger on,

My only friend shall be the moon,

Which on my sadness shone,

When other friends are gone.

79/100 左京大夫顕輔 – Sakyo no Taiu Aki-suke

秋風にたなびく雲の絶え間より もれ出づる月の影のさやけさ

SEE how the wind of autumn drives

The clouds to left and right,

While in between the moon peeps out,

Dispersing with her light

The darkness of the night.

81/100 後徳大寺左大臣 – Go Tokudai-ji Sadaijin

ほととぎす鳴きつる方をながむれば まだ有明の月ぞ残れる

THE cuckoo’s echo dies away,

And lo! The branch is bare

I only see the morning moon,

Whose light is fading there

Before the daylight’s glare.

86/100 西行法師 – Saigyo Hoshi

嘆けとて月やはものを思はする かこち顔なるわが涙かな

O’ERCOME with pity for this world,

My tears obscure my sight;

I wonder, can it be the moon

Whose melancholy light

Has saddened me to-night?

Which poem is your favorite?

Source: A Hundred Verses from Old Japan (The Hyakunin-Isshu) translated by William N. Porter (1909) – Sacred Texts