What a sustainable life!

Kimono 着物 literally means “a thing to wear” in Japanese. Until Japan opened its country to the Western world in 1868, everybody in Japan wore kimono.

…

I grew up dispising kimono as outdated when I was in Japan. Only after I moved to the US, I became more interested in and more attached to this unique form of dressing.

In the tea ceremony, the rules for each movement of the body are based on the assumption that the practitioner is dressed in kimono. For example… With the long sleeves of kimono, how would you move your arms so that you would look most graceful when pouring hot water into the tea bowl?

When I started practicing tea ceremony 13 or 14 years ago, I thought wearing kimono for every practice would be the fastest to improve my practice. Or maybe the other way around. I might have decided to practice tea ceremony so that I can wear kimono more often.

Since then, whenever I went back to Japan, I would bring back my mother’s old kimono. She is shorter than I am, but kimono is made longer so that the length can be adjusted depending on the height of the person. One crucial point is the length of the arms. Luckily my mother has long arms for her height, about the same length as mine.

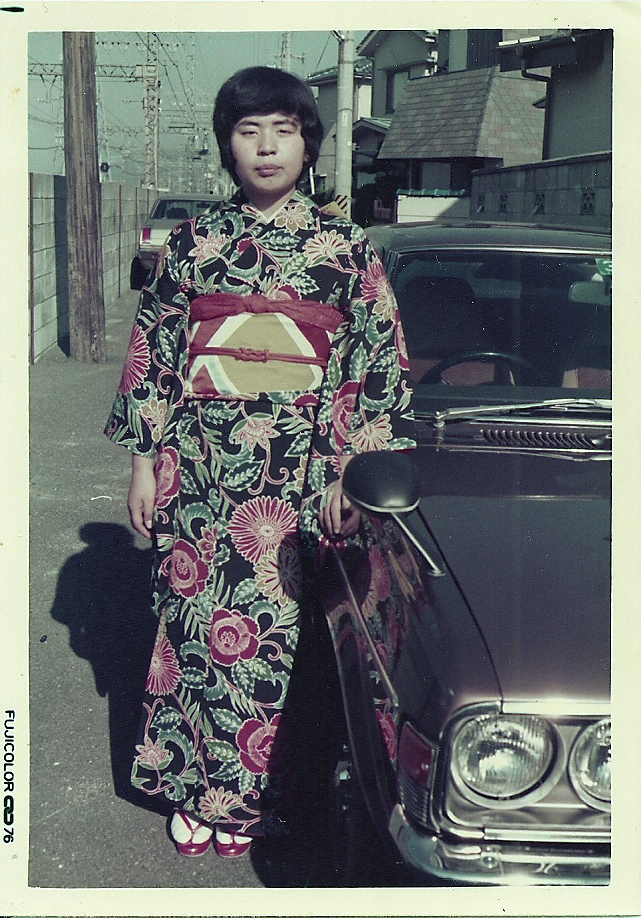

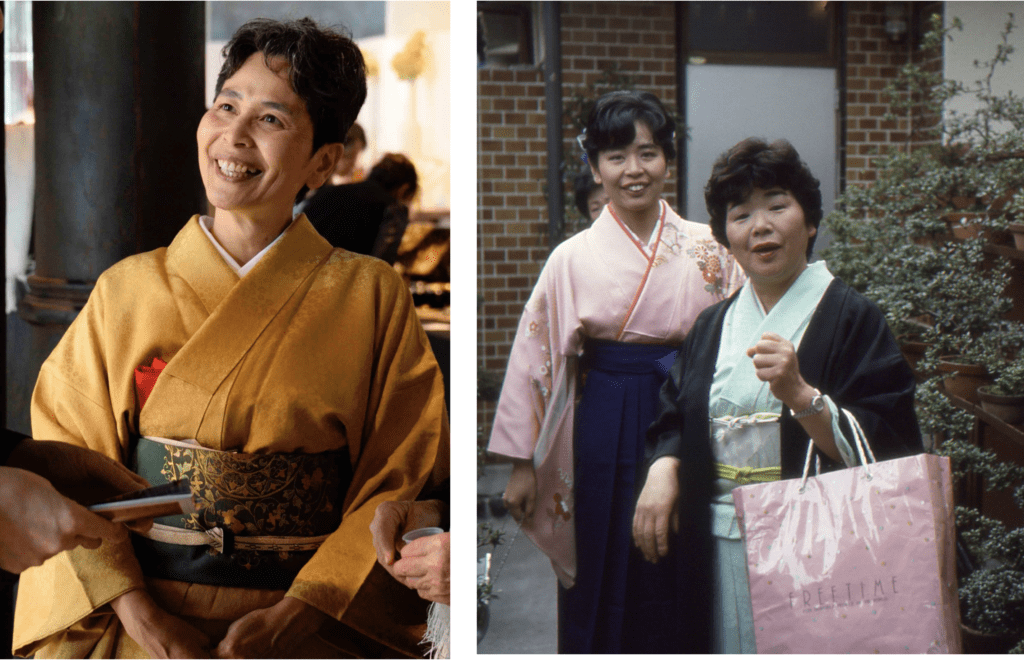

The photo above is my mother’s most casual kimono. The fabric is silk pongee, called tsumugi 紬 in Japanese.

I remember her doing laundry wearing this kimono. I must have been 3 years old. It’s now hard to believe that she did such house chores in kimono. But over half a century ago, kimono was more prevalent in Japan. Kimono was the default wardrobe in my grandmother’s days!

This kimono is a more formal one. Also made of silk, but the texture of the fabric is smoother and softer than the first one. The small crescent pattern is spread all over. This type of design is called komon 小紋.

I remember she wore this kimono when she came to kindergarten to pick me up after my first overnight trip.

This black kimono with arabesque pattern has a distinct texture. The fabric is thin and light, unique characteristics of Oshima Tsumugi 大島紬.

This was my mother’s spring kimono. The pattern is cherry blossoms, and I always wear this for tea gatherings in the spring.

Can you believe the kimono my mother was wearing (the photo on the right) and the one I’m wearing (the photo on the left) are the same kimono?

My mother’s kimono used to have quite a light greenish color. Over time stains appeared and she got tired of the color. No, she didn’t throw it away. Rather, my mother took it to a professional whose speciality is to redye kimono. He redyed it to golden yellow. With this color, the old stain disappeared!

Now I wear this kimono in the autumn.

Silk fabrics are amazingly durable. With the way kimono is structured, people in different sizes can wear the same kimono, like my mother and I. By redying, an old kimono is reborn with a totally new look!

The era of mass production and mass consumption is over. By enjoying my mother’s kimono in daily life, I’m ever more appreciating what kimono teaches me: The value of a sustainable life.